The Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging

7 November 2023

To explore the intersection of AI and DEIB, IIC Partners interviewed Sandra Rosier, C-Suite advisor, seasoned DEIB speaker, and accomplished tax advisory professional with a specialization in capital markets.

Sandra provides an in-depth exploration of the subject and is not afraid to call out the devastating harm created when AI is not used or created in ethical and inclusive ways.

Introduction

“The idea of this interview was born from a reflection within our Financial Services & Insurance Practice Group on the potential links between artificial intelligence (AI) and diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging (DEIB).

Our global teams have often discussed the benefits and risks AI poses to the finance and insurance sectors but when it comes to DEIB, we have been concerned that the balance may lean toward the negative side due to AI drawing upon biased data.

To explore this critical subject, we interviewed Sandra Rosier, C-Suite advisor, seasoned DEIB speaker, and accomplished tax advisory professional with a specialisation in capital markets. Sandra explores the intersection of AI and DEIB in-depth and is not afraid to call out the devastating harm created when AI is not used or created in ethical and inclusive ways.

Sandra delivers her valuable insights with a searing clarity and her ideas for an improved, DEIB-forward approach towards AI, along with clear actions that executives can take to create a diverse and inclusive workforce, make this piece a must-read.”

Romain Girard

Financial Services & Insurance Practice Group Leader

About The Author

Sandra Rosier is a senior tax consultant who advises institutional clients and investment organizations on tax strategy and risk management in Toronto, Canada. Previously, she was the Global Head of Tax at BentallGreenOak, a leading real estate investment and property management company headquartered in New York with offices in 12 countries and $85 billion in assets under management. In addition to her DEIB thought leadership work, Sandra is active on the BlackNorth Initiative’s Mentorship & Sponsorship Committee (an organization committed to increasing the representation of black people in the boardrooms and executive suites across Canada). She is a non-board member of St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation’s audit committee and sits on the Board of the West Toronto Community Legal Services clinic.

01. What are some of the most significant challenges presented by AI, particularly in relation to DEIB?

The first challenge with artificial intelligence is that there is no commonly understood definition of “artificial intelligence” or AI. There are many different kinds of AI, which means that it has become a catch-all term for everything from the apocalyptic robots in the Terminator movies to customer service chatbots.

Having a baseline understanding of what AI means can enable us to engage in more constructive discussions. A helpful and straightforward definition of AI can be found in the Oxford Dictionary: Artificial intelligence is the “Theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks normally requiring human intelligence…” The New York Times has also put out some outstanding educational materials and thought pieces on AI in print and podcast formats that are worth exploring.

The most significant concern with AI currently, even among prominent AI scientists and evangelists, is that AI could result in the annihilation of humankind. Perhaps less dramatically, the fear that AI can have harmful effects on human beings has proven to be justified. By comparison to Law or Medicine, the IT industry remains obstinately white and male, at least in the Western world. The AI industry reflects this dynamic, which has implications. What happens when a largely homogenous cohort of AI scientists and investors – who originate from the same socio-economic milieu, hail from the same elite American academic institutions and share a common worldview and political ethos – fund and design a revolutionary new technology that could have unfathomable effects on our collective futures?

When there are limited perspectives during the creative decision-making stages, one potential bad outcome is that biases get baked into algorithms such that entire segments of the human population are omitted. The ginny is already out of the bottle. We are living today with AI tools that have automated discrimination in the name of efficiency.

Once these harms occur, there seems to be an alarming reluctance to course-correct. Cue the notorious examples of facial recognition software that continues to exclude and harm non-white individuals. The bad outcomes that can result from homogenous AI leadership and development teams are not always predictable. Early iterations of generative AI, such as ChatGPT, have malfunctioned in bizarre and destructive ways, echoing antisemitic, racist and misogynistic rhetoric from the vilest reaches of the Internet. I find it interesting that nobody intended, much less anticipated, these kinds of self-defeating and embarrassing missteps. That’s what makes the tyranny of echo chambers so pernicious. You can only see and hear the people who are locked in the room with you.

The paradox of AI is that it is a generative technology that is “intended” to simulate the best of human intelligence, yet it can be profoundly destructive when its architects are all hatched from the same clone pod. My hope is that the mistakes that were made and even those that continue to be made in this dawn of AI will teach us some valuable lessons about the importance of democratising this rapidly growing sector. To achieve truly human AI, people who represent the various dimensions of diversity must participate in the decision-making, development, design and regulation of AI.

02. Can you provide examples of unintended consequences created by AI that disproportionately affected specific demographic groups?

Can AI ever truly be neutral if it literally encodes human perspectives? When you are dealing with large data sets and analytics, is it enough to say “Sorry, we don’t lend to businesses in that neighbourhood, it’s just math.” Biases in the use and manipulation of data predate AI. Most of us are familiar with the stories of intentional discrimination by insurance companies denying coverage or charging usurious premiums on the basis of race, ethnicity or gender.

Some of these cases are more recent, such as a 2022 lawsuit in Illinois alleging that an insurance company systematically denied coverage to Black customers on the basis of race by using predictive data to filter out market segments that the insurer deemed a “bad risk”. In its 2020 public consultation summary report on the Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices (UDAP) Rules, the Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario (FSRAO) cited a number of unfair and discriminatory industry practices reported by stakeholders, including the use of credit scores as a basis to deny insurance coverage. The distant and not-so-distant examples of AI discrimination demonstrate the potential that the design and use of AI algorithms in insurance and finance could result in discriminatory outcomes such as denial of coverage, higher premiums, over-denial of loans, higher interest rates on loans and poor customer service.

In 2022, the Society of Actuaries published a surprisingly readable paper titled “Avoiding Unfair Bias in Insurance Applications of AI Models.” The paper does a great job of mapping out the ‘hierarchical levels of AI” adoption in insurance and the ways unintentional biases can emerge through the various applications of AI. The use of AI in financial services and insurance is still in the ‘emergent’ category given that the technology itself is in flux. However, some more established AI applications are now commonly used in insurance, for instance, in data modelling, marketing, fraud prevention, predictive analytics and customer service.

It’s worth noting that financial services and insurance are heavily regulated industries that are subject to laws which prohibit outright discrimination on the basis of factors such as race, gender and religion. In other words, existing legislation will likely cover some aspects of AI discrimination. Industry standards, market practice, competition and reputational risk also go a long way towards encouraging socially responsible corporate behaviour. There is an inherent tension between a) the responsibility of governments to protect vulnerable populations from unfair practices and outcomes, and b) industry norms based on the legitimate data-driven assessments of risk which determine market pricing. AI does introduce new variables that regulators, including FSRAO in Ontario and U.S. federal regulators, are currently trying to catch up to. It will be interesting to see how regulators navigate these issues and whether they are able to strike a constructive balance.

Pending the enactment of a cohesive set of regulations, organizations should take a pre-emptive approach to AI risk management. They should be deploying executive leadership training in AI today, in the same way as this evolved in ESG and DEIB. We can remember a time when some detractors dismissed ESG and DEIB as a fad. Obstinate resistance is the opposite of a reasoned position. I’ve always thought that you cannot convincingly argue against new technology, different business models, or even an alternate worldview from the outside, without having a functional understanding of the thing that you are disavowing.

It is critical that leaders be equipped to have intelligent conversations about AI to enable them to ask informed questions about the opportunities, impacts and risks of AI to their business. Delivering AI education and training to leaders before the train has left the station will not only enable leaders to gain early mover advantage but also empower them to make smarter and more prescient business decisions about AI.

03. How does economic uncertainty impact DEIB and ESG initiatives? How does this relate to the rise of AI?

The progress of social justice is not linear. It has always been susceptible to the vagaries of public sentiment and the political mood at any given time. That’s exactly what we are experiencing now with the waning public support for equity-based activism, DEIB initiatives and in particular the increased hostility towards anti-Black racism. To paraphrase Frederick Douglass, power concedes nothing without a fight. I believe that we are living the backlash that would inevitably have followed the George Floyd-inspired BLM euphoria even without an economic downturn. Certainly, the downturn has exacerbated the sharp societal divisions that we are currently experiencing. The argument that ESG and DEIB are part of a left-wing genocidal conspiracy to destroy capitalism and white people has found a foothold in public discourse as rational propositions that are worthy of debate.

Our collective social and corporate priorities have shifted. Corporations are in survival mode, bracing for the impact of the next round of interest rate hikes. In that kind of climate (no pun intended) discretionary corporate responsibility programs like ESG and DEIB are the most susceptible to de-prioritization and cost-cutting. This is unfortunate because now is when organizations should be doubling down on their commitment to DEIB, allocating DEIB funding to AI preparedness and investing in equitable AI.

Peter Trainer, an AI consultant and speaker, recently observed in an opinion piece decrying the lack of diversity in AI, “Artificial Intelligence isn’t Auto-Magic, it’s opinions embedded and amplified by code. Full-stop.” We know that AI can exacerbate inequality. On the flip side, organizational leaders have an opportunity to ensure that AI technologies contribute to bridging the gap between societal promises of equality and the actual experiences of marginalized communities. Trainer declined to officiate a prominent AI awards ceremony where the panel of judges were all white men and the overwhelming majority of nominees were men.

Calling out or declining to participate in events with no diverse perspectives at the table is one of the most powerful ways that leaders can advocate for equity and representation. In his opinion piece, Trainer outlines key areas that he believes “we need to address immediately to stop the world from being formed in the image of the tech-bro.” The first area is homogeneity in AI decision-making.

There is unlimited potential for using AI to improve representative hiring in the financial services and insurance sectors. However, AI outputs are only as good as the inputs. And inputs need to come from teams that think differently, have diverse backgrounds and come from varied lived experiences. It is now a truism that the richness of diverse perspectives generates better results. Industry must also get really good at asking the right questions to generate the richest data set. It’s not enough to chase information. Rich data yields unexpected insight. When you’re trying to identify outstanding talent from racialized and underrepresented groups, the right question is not how many Black students have graduated from X university in the past two years. The right input question is: in the U.S., what areas do Black women excel significantly above average relative to the rest of the population? That question will yield valuable insight, namely: per capita, a higher percentage of Black women is enrolled in college than any other group, including Asian women, white women and white men according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Organizations that are truly committed to inclusive hiring must develop strategies to leverage big data and AI in order to generate valuable talent pool information of this nature. The global majority talent is out there. For organizations that can master the art of asking the right questions, AI can deliver unprecedented tools to find that talent.

When you look around the room, who is sitting at the boardroom table? Who is occupying C-suite offices and do they all look alike? Financial services organizations that are starting to shore up their internal AI capabilities and subject matter expertise will reap the benefits in the near future. Boards and senior leadership teams should be looking at bringing multidisciplinary talent with specialized AI or big data technical skills as well as experience in disciplines like HR, risk, audit, ESG or compliance/legal functions. AI business strategy should be integrated with the DEIB Action Plan to ensure that there is equitable representation across AI teams and an anti-bias diligence process to vet externally sourced AI tools.

04. What are your thoughts on AI regulation?

A coordinated, cohesive and intelligent regulatory response to AI is desperately needed. As demonstrated by history, at every significant frontier of human innovation, some humans have placed greed and ambition ahead of the best interests of humanity. The future consequences of self-interested and single-minded decisions made by a handful of self-appointed denizens of AI could be disastrous for all of us. The challenge, of course, is that regulators may be ill-equipped to meet the AI moment. After all, it is in our nature to destroy what we fear. There is a real risk that regulatory intervention will miss the mark, either by stifling innovation or failing to address the dark side of AI, or both.

AI technology is moving at a remarkable pace. It has the potential to revolutionize how we work, learn, communicate and deliver services. Unfortunately, even at this fledgling stage of the technology, the so-called AI industry (the early movers, tech giants, start-ups, VCs and investors) has demonstrated that it cannot be trusted to be both innovator and steward of this realm. Earlier this year, we saw the launch of generative AI platforms by OpenAI, Google and Microsoft, among others. Troubled by the unchecked pace in the development of “AI systems with human-competitive intelligence”, a number of tech industry leaders, including Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak, signed an open petition letter in May 2023, warning against the “profound risk to society and humanity” posed by AI and asking for a thoughtful six-month pause to the AI arms race. While the idea of a pause strikes me as rather futile (pause to what end?), even these men understand the need to tread carefully, given the potentially apocalyptic power of AI technology.

According to Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT), a seismic disruption of labour markets is not only inevitable, it is desirable because “the marginal cost of an AI doing work is close to zero” relative to the cost of highly skilled and highly paid labour. For Altman, millions of knowledge management jobs lost is simply a market adjustment, the natural outcome of the low cost of AI work. This begs the question, “low cost” for whom? And how do Altman and his ilk define cost?

The bad outcomes in AI are not just about the end of times that AI could engender, the harm done by AI tools like generative AI bots gone rogue or the discriminatory results from facial recognition software encoded only with white faces. In determining how to regulate AI, we must also consider how AI might impact or displace industries and who can get hurt in the “manufacturing” stages of the technology.

A Times investigation found that OpenAI paid Kenyan workers less than $2 an hour to filter out traumatic content from ChatGPT. The irony is that Altman actually supports the regulation of AI. In fairness, such ethical quandaries are not unique to OpenAI. The news media that we consume is already produced using AI. The Associated Press, Reuters and Washington Post all use AI writing tools, which raises a number of concerns around accuracy of information, IP and truth in journalism. However, ethical and legal concerns about the content published by established news organizations pale by comparison to the threat of online content farms that churn out unvetted and false information, in addition to violent and harmful content, on a continuous basis. As AI continues to evolve, it is not a question of whether but when and how humans will make mistakes. Most mistakes are forgivable and recoverable. Others are deliberate and can be catastrophic. That is the most compelling argument for regulating AI.

Innovation will always outpace regulation. There is always a place for industry self-regulation, which in some cases, can help to temper and reign in the overzealousness of regulators, especially in the emergent stages of a new technology. Recruitment firms and Financial Services can get ahead of the regulatory curve by developing AI risk management frameworks and ensuring they are equipped and prepared for AI self-audits. As these organizations are incorporating AI into business planning and strategy, they should be thinking about AI risk-assessment tools and mitigation plans and hiring or retaining strategic and operational AI expertise to develop AI integrated business models and governance frameworks.

05. What are some DEIB considerations when thinking about employee retention?

Employees, irrespective of background, stay in workplaces where they experience psychological safety, belonging and purpose. Conversely, people leave workplaces where they feel unsafe, excluded and adrift. A May 2023 Indeed poll reported that 49% of Black workers surveyed said they wanted to quit their jobs. The reasons were predictable. The main reasons cited by Black workers for their disenchantment: lack of transparency around compensation, misalignment between personal and corporate values and lack of diversity in the C-suite. A Gallop study conducted in March 2023 provides additional insight into the high rate of disaffection among that segment of racialized workers. Gallop reported that nearly 70% of all employees did not feel that their organization was committed to improving racial justice and equality in their workplaces. 25% of those polled indicated that issues of race and equity were not openly discussed.

What is interesting about the last two Gallop poll percentages cited above is that they are not specific to racialized workers. It turns out that trust or the lack of it, is an accurate measure of culture. Nothing erodes the trust of workers from racialized and underrepresented communities more than DEIB commitments that go unfulfilled. Nothing corrodes the morale of all workers more than corporate value statements that are fundamentally misaligned with the actions of leadership and the lived experiences of workers on the ground. What this data shows – particularly on the other side of the George Floyd-inspired global reckoning on race, the pandemic work-from-home paradigm shift, and the corporate promises of DEIB and flexibility – is that a majority of workers no longer believe what employers are saying about DEIB. As James Baldwin famously said: “I can’t believe what you say because I see what you do.” Retention basically comes down to trust.

When you are the only one in the room or one of the few in the entire company, it is not a question of whether you will encounter friction when you’re trying to do your job, it is a question of what form that friction will take, whether it is a colleague touching your hair, an unwelcome comment about your homemade lunch, your exclusion from participation in the social norms of the majority culture, your boss not being able to “relate” to you, or a member of the executive team mistaking you for cleaning staff.

Imagine being a highly qualified Vietnamese-Canadian woman in an organization where these things happen to you regularly, all of the senior leadership is white and male, and the DEIB strategy is regularly trumpeted on LinkedIn? The cumulative impact of this kind of workplace experience on a racialized person can be profound, even if no harm is intended. That friction is literally a drain on human capital, an organization’s most valuable resource. Is it any wonder that people want to leave workplaces where they are made to feel like outsiders and cannot trust that they will be rewarded fairly for their work?

In my experience, the vast majority of progressive and empathetic white leaders assume that racialized employees do not experience harm or any friction within their organizations, oblivious to the irony that their very race and social programming shield them from being able to see or even acknowledge these experiences. It is not easy for your racialized employees to talk about their negative experiences in the workplace, precisely because such disclosures are too often met with silence, denial or inaction. Leaders must acknowledge and empathize with the unique challenges faced by employees from racialized and other underrepresented communities. Because most of the harm is systemic and/or unintentionally delivered, often by decent people, it is critical to focus on impact and harm-reduction and to deprioritize intention. Leaders must be intentional about taking concrete actions to eliminate the friction that these employees experience so that they are not merely protected from harm at work, but also able to operate at their best and thrive.

The most important thing that leaders can do to retain people is to re-establish trust where it is eroded or continue to build a strong foundation of trust. Always do what you say and don’t say it if you’re not going to do it. Your employees are watching. Committing to a representative workforce and leadership that reflects the community at large will enrich your culture and make you better. Decide what kind of organization you want to lead and be honest about whether DEIB is in fact a priority for your business. If DEIB is a priority, DEIB strategy should be action-oriented, attached to good-faith metrics and anchored in time-based targeted objectives.

Senior leadership should not only signal that DEIB is a core value, but should also make it clear to the executive team and managers that all leaders within the organization are responsible and accountable for DEIB execution and success. Accountability tools should never be punitive, which is a recipe for resistance and resentment. Accountability should be tied to reward incentives, such as recognition awards and bonus incentives that financially compensate leaders who walk the talk. A DEIB Action Plan that fosters trust, goodwill, belonging and safety should be transparent and crystal-clear to everyone from the top-down and from the bottom-up.

The stats are in. For most employees DEIB training is either pointless or non-existent. We must be able to have adult DEIB conversations in the boardroom if we want to achieve justice, equity and belonging for the benefit of all of us in the workplace. Set your leaders up for success by equipping them with robust no-bullshit DEIB training that eschews insipid, feel-good unconscious bias rhetoric. Let’s create a safe space for people managers and senior leaders to build cultural competency and racial efficacy. These are critical leadership skills in 2023. Either we give people credit for their ability to withstand uncomfortable truths, or we risk fostering an environment where racism and discrimination are never discussed, and therefore, tacitly sanctioned. DEIB training must aim to disrupt, dismantle and deconstruct white supremacy, misogyny, transphobia, homophobia and other systems of oppression. Those words are scary as heck until we are sufficiently immersed in their meaning to be able to deploy them in conversations without flinching, even if we have differing views.

Specific actions that leaders can take today to ensure they are managing their teams in a DEIB-supportive way:

1. You cannot fix what is not named or discussed. Bring in highly credentialed DEIB professionals with lived experience to facilitate DEIB discussions and training about the intentional and unintentional ISMs that occur in the workplace and how they undermine culture and productivity.

2. Look to senior leadership to lead and be accountable for the DEIB Action Plan, with HR playing a supporting role.

3. Have the courage to elevate the recruitment, retention, championing and promotion of racialized people in your DEIB Action Plan. Gender equity is not a proxy for meaningful diversity if your leadership remains white.

4. It should not be the job and responsibility of employees from racialized and underrepresented groups to fix what is broken in an organization or to take on the additional uncompensated emotional labour and politically risky work of DEIB strategy. Their participation must be optional. Leave it up to them to volunteer. Do not ask.

5. For organizations in the U.S., build a talent pipeline by holding events at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

6. Create internship opportunities for underrepresented groups.

7. Partner with global majority business groups and professional associations for recruitment purposes.

8. Create formal mentorship structures; they work and typically do not occur organically for cis and queer women, racialized employees and employees from other underrepresented communities.

9. Identify outstanding employees from underrepresented groups for leadership acceleration programs.

10. Take responsibility for your own growth and education. The 48 Laws of Power is not the only seminal leadership book ever published, although it’s a classic. As well as Machiavellian political mastery, the leaders of our current age must be culturally agile. Out of Office, White Fragility, How To Be An Anti-Racist, I’m Not Yelling, Think Again, and (for Canada/US) Living Resistance: An Indigenous Vision are six recommended books that I believe organizational leaders should have read or be familiar with in 2023. You don’t have to like these books or even be interested in them, but they are seminal readings that will gift you the critical vocabulary needed to engage in the conversations that are being had today around corporate culture-building, DEIB (inclusive of Indigenous perspectives) and the ever-shifting definition of “workplace”.

11. Stay the course on DEIB. Progress steadily and relentlessly towards incremental change that will lead to transformation rather than going for a quick Disney ending. DEIB work is a journey, not a destination.

06. Final Thoughts

When AI fails, there is a tendency to anthropomorphize the technology. The reality is that AI is neither virtuous nor unvirtuous, good or evil. AI is an extraordinary tool but still merely a tool, like a stick or a calculator. AI is no more responsible for the harmful outcomes or bad answers that are generated than the stick and calculator. Right now, unfortunately, we have a polarized dynamic of whistleblowers and detractors versus evil AI tech giants. In that climate, there is a heightened risk that regulators over-reach to try and control a technology that they do not understand and end up ruining the fun for everybody. My hope is that regulators catch up quickly and act judiciously in ways that incentivize good corporate behaviour without impeding innovation. Ultimately, market actors, including AI producers, investors, industry participants and the companies that will consume AI, have the most crucial role to play in how, by whom and for whom the technology is designed and implemented in the real world.

A NOTE FROM IIC PARTNERS: A special thank you to Sandra Rosier for taking the time to share these incredible insights and learnings. We appreciate you more than words can express!

Sandra Rosier’s DEIB Resource List

Organizational

The Waymakers: Clearing the Path to Workplace Equity with Competence and Confidence, Tara Jaye Frank

The Inclusive Organization: Real Solutions, Impactful Change, and Meaningful Diversity, Netta Jenkins

I’m Not Yelling: A Black Woman’s Guide to Navigating the Workplace, Elizabeth Leiba

The Anti-Racist Organization, Shereen Daniels

So You Want to Talk About Race, Ijeoma Oluo

Article: The high price of silence in the workplace: The Ugly Truth: Everyone Wants An Anti-Racist Workplace, But No One Wants To Speak Up

Article: How Companies Can Be Anti-Racist

Article: Why Diversity Programs Fail

Interpersonal

White Fragility, Robin Diangelo

How to be an Anti-Racist, Ibram X Kendi

White Women: Everything you Already Know About Your Own Racism and How to do Better, Regina Jackson and Saira Rao

My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, Resmaa Menakem

Article: How Racism Affects the Brain and Mental Health

Article: 16 Things Black People Want Their White Friends To Know

Historical/Societal

The Long Road Home: on Blackness and Belonging, Debra Thompson

The Sum of Us, Heather McGee

Caste, Isabel Wilkinson

The Skin We’re In, Desmond Cole

Shame on Me, Tessa McWatt

21 Things You May Not Know About the India Act, Bob Joseph

Article: The Economic Cost of Racism

Additional antiracism resources, including podcasts and films:

Multimedia Anti-Racist Starter Pack

Ibram X Kendi’s NYT Anti-Racism Reading List

Toronto Public Library (National and International Resources)

Canadian Women’s Foundation: Resources for Ending Anti-Black Racism

Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion — Anti-Racism Resources

Harvard Compilation of Resources

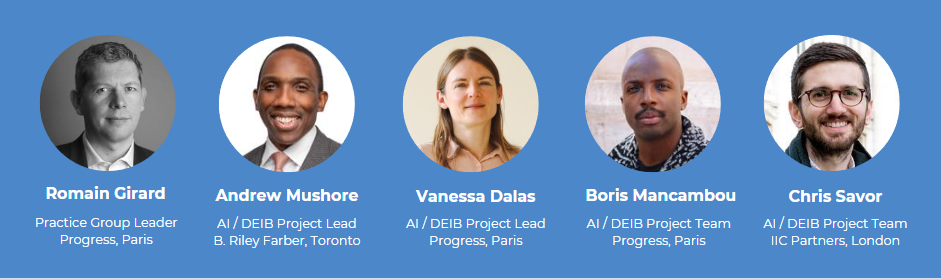

IIC Partners AI / DEIB Project Team

About IIC Partners

IIC Partners is a top ten global executive search organization. All IIC Partners member firms are independently owned and managed and are leaders in local markets, developing solutions for their client’s organizational leadership and talent management requirements.